It's hard to believe, but we've come to a point in history when you could create an animated movie about talking appliances and nobody would think you were crazy. This can largely be chalked up to the influence of living legend John Lasseter, whose popular Pixar films have not only changed the way an entire generation of animated pictures are made, but often display his fascination with telling stories based on the separate lives of things around us we pay little attention to.

The Brave Little Toaster is such a Lasseter-eseque film that I had suspicions he had more to do with it than the movie's credits let on. Those suspicions were confirmed in a 2006 CNN piece written by John himself. Instead of Toy Story, his original film idea was to make this.

| Tron was made by a different

part of the studio, unrelated to animation. This young

live-action executive named Tom Willhite picked me out of

the group because I kept talking to him about how we

could use this new technology in animation. So he let me

and a colleague put together a 30-second test, combining

hand-drawn, two-dimensional Disney-style character

animation with three-dimensional computer-generated

backgrounds. I was so excited about the test, and I wanted to find a story that we could apply this technique to in a full-blown movie. A friend of mine had told me about a 40-page novella called "The Brave Little Toaster," by Thomas Disch. I've always loved animating inanimate objects, and this story had a lot of that. Tom Willhite liked the idea, too, and got us the rights to the story so we could pitch it to the animation studio along with our test clip. When it came time to show the idea, I remember the head of the studio had only one question: "How much is this going to cost?" We said about the same as a regular animated feature. He replied, "I'm only interested in computer animation if it saves money or saves time." We found out later that others had poked holes in my idea before I had even pitched it. In our enthusiasm, we had gone around some of my direct superiors, and I didn't realize how much of an enemy I had made of one of them. I mean, the studio head had made up his mind before we walked in. We could have shown him anything and he would have said the same thing. Ten minutes after the studio head left the room I get a call from the superior who didn't like me, and he said, "Well, since it's not going to be made, your project at Disney is now complete. Your position is terminated, and your employment with Disney is now ended." So, yeah, I was fired. But you have to understand, I never told anybody, because this was my identity. The only thing I'd ever wanted to do was work for Disney. I was so excited, and pushing, and I didn't play the political game. I was devastated. I now realize all this stuff happened for a reason. As I put together my pitch for "The Brave Little Toaster," I had started looking for people who could do computer animation. That led me to Lucasfilm, because they had this computer division that had some of the world's best computer scientists. I even went up to San Rafael and visited Ed Catmull and Alvy Ray Smith, the two guys who started the group. Ed and Alvy had approached Disney Studios to try get them interested in computer animation, without much success. But now they saw me inside the studio starting to talk seriously about making films with computers, and they got excited that finally Disney might be interested. What they didn't realize was that it was really just me pushing to try to get something going. Soon after I was fired, I went down to a computer graphics conference at the Queen Mary in Long Beach. I'll never forget it. I saw Ed give his talk, and when he saw me he came up all excited and asked, "How's Toaster?" All I could say was, "It got shelved." I didn't have the guts to tell him I got fired. So he asked what I was doing next, and I told him I wasn't sure. |

Ed brought John on board at Lucasfilm, and from there Pixar was founded. Even if you hate the toaster, and don't know why you clicked to read this article, you at least have to give it props for indirectly causing Pixar's existence. If it hadn't gone on its Incredible Journey there would be a hole in space-time.

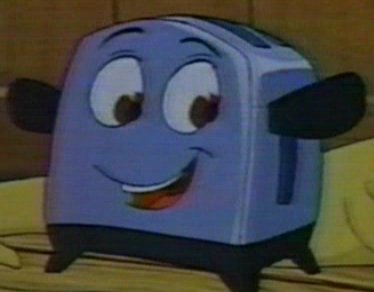

Note: I'm referring to the toaster as an "It" because it's my opinion they didn't intend for it to display an identifiable gender. The toaster has the voice of a woman (Deanna Oliver, that awesome Animaniacs writer), but the voice itself as well as the toaster's appearance seem to be intentionally vague. There is one point in the film where Toaster is addressed as male, when Radio shouts "I think he fell into the river!"...but I think that was an oversight, as that's the only time.

Look, if Toaster's a dude, then he's a creepy dude. Let's just leave it at that.

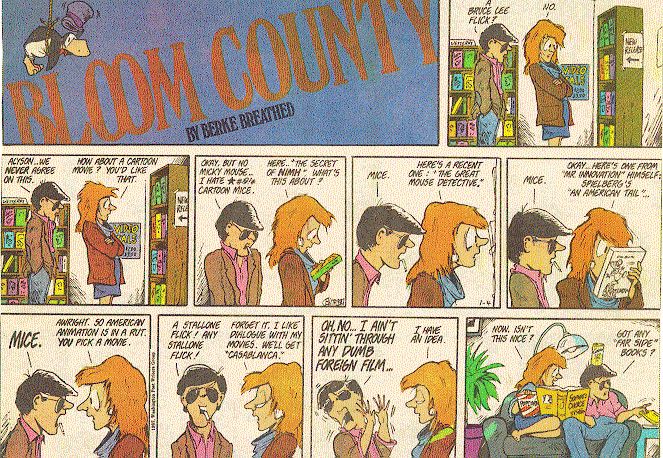

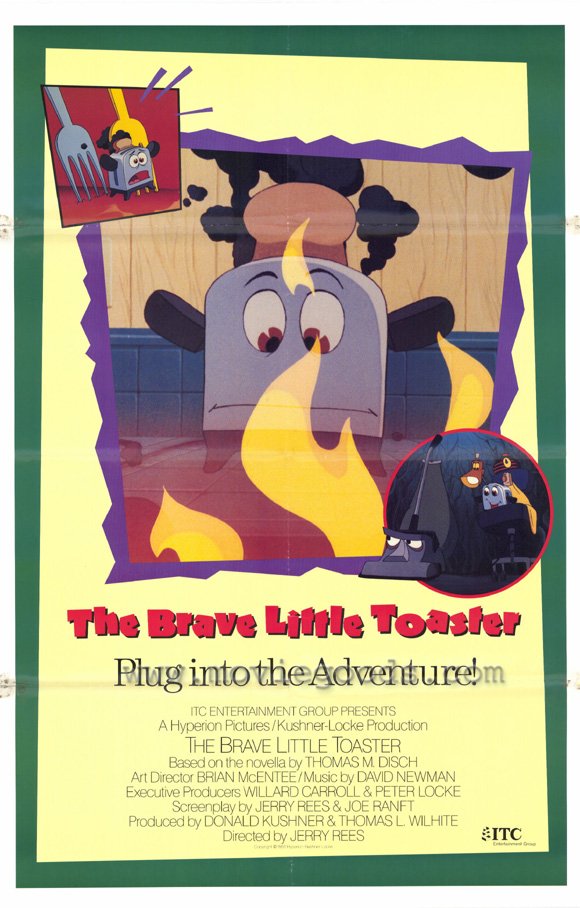

In the 1980's there was the apparent belief that if an animated film wasn't about a mouse, a cat, or a dog, or any combination of the three, nobody would want to see it. In that day and age, pitching a movie about a little mermaid was a hard sell, but to propose a film about a toaster was lunacy. Under the funding of a couple of outside investors it eventually got made, but also under a significantly smaller budget and under Hyperion Pictures, a new independent film company founded by two ex-Disney employees.

"Small" meant $2.3 million--four TV cartoon episodes would have cost about the same. And Disney barely did anything with the movie once it was completed. It made its big screen debut at the Sundance Film Festival and its debut everywhere else on the Disney Channel in 1988. It also had a very small, sporadic theatrical tour, appearing in one art-house theater every few months for the next four years.

Despite all the production obstacles against it, I can't think of anything this film did wrong. Yeah, the characters are appliances, but they're all three-dimensional and sympathetic. The orchestral music score is beautiful and sounds like it should cost ten times what they apparently paid for it. The editing and sense of timing is unequaled. There are songs, but they never feel forced and they're placed in exactly the right places, where they enhance the plot rather than derail it for a few minutes. Wang Film Productions handled the animation, and they normally do TV cartoons, but this is among their best work.

The only element this film gets wrong is that the main character is a talking hermaphrodite toaster with giant Mickey Mouse eyes. Unfortunately, that was a big thing to get wrong.

As far as casting went, they just hired the entire Groundlings troupe at the time, which included Jon Lovitz and Phil Hartman. (The exception was the vacuum--he ended up with the voice of Tony the Tiger.) Lovitz and Hartman were hired by Saturday Night Live two weeks after they finished recording for Toaster. But before he was a star, Hartman was the Jack Nicholson Air Conditioner.

There are various moments in this movie that tended to stick in children's minds, and the air conditioner exiting the film early by throwing a fit and blowing up is one of them. Not every family picture begins like that, and The Brave Little Toaster made it clear early on it wasn't your average soft kiddie flick. Because the main players were all machines, they could be placed in situations more harsh and frightening than would be allowed with human beings or animals.

This isn't to say the film is depressing as a result of this--not per se. It's just more realistic (well, as realistic as a concept like this can be). Normally, empathy for appliances would be a hard sell outside of believers in animism, but the fact that it's not a softened film works better for the plot. If we fear the danger these things are getting into, we empathize with them and can get lost into the movie. And there are several subtle character arcs through the film that flesh them out: Toaster decides to be nicer to Blankie after realizing how lonely Blankie is (via a sad scene involving a misled flower), Lampy develops courage by turning himself into a lightning rod to recharge a battery during a thunderstorm, and Kirby--well, we'll get to him....

All the appliances are named after what they are ("Blankie," "Lampy"), with the exception of the vacuum cleaner, named "Kirby" after the brand name. Like a grumpy old man, Kirby has a tendency to hide his true feelings on everything and instead respond by lashing out at others. We get light hints he's actually a fragile being on the inside and has built this wall as a personal defense. The ultimate Kirby moment comes when everyone has to cross a dangerous waterfall, and they all fall in except for him. After a moment of hesitation, Kirby suddenly rushes down the waterfall himself and saves everybody, then of course denies what he just tried to do. The film's moments of self-discovery are handled well and never come off forced or ham-fisted.

Now that we've connected with the characters, it's time to ramp up the danger! After the waterfall, they stumble into quicksand (despite this being an old cartoon cliche, it's done effectively) and are "saved" at the last minute by a machine parts collector. They soon find themselves in the backroom of his repair shop, greeted by Frankenstein-ish gadgets and a Peter Lorre hanging lamp (also voiced by Hartman). This could have been the scariest portion of the film, but they tamed it by making the parts collector as unscary as humanly possible.

He's a fat tub of lard named Elmo, but his devices react in total fear toward him, as any one of them could be taken apart by his Tools of Death next. One customer of Elmo's requests a blender motor, and the resulting motor-extraction scene is staged like something out of a "Saw" film. Then the customer comes back and wants some radio tubes, which could mean the end of Radio!

The appliances escape in the end by scaring the bejabbers out of Elmo, and head on to the city, where they find....wait.

I haven't even mentioned why they've been going to any of these places, have I? They're on a mission to be reunited with "The Master"--the small boy who once lived at the now-abandoned cottage where they once lived as well. It's similar to the bond in Toy Story, except it's kind of tragic to see. If a toy loved a little kid, the little kid could be expected to love the toy just as much. But no mentally stable kid has ever been attached to his toaster.

At the point the appliances enter the city, the movie cuts to the first real glimpse of "Master," and we see just how long it's really been since he left that house. Only seen in memories as a child, here he is in real time about to leave for college (and voiced by Wayne Kaatz, another awesome Animaniacs writer). The good news is that he's looking for some cheap appliances to stock his dorm. The extra-aggravating news is that he's going BACK TO THE OLD HOUSE to get them. The entire journey was for nothing, yet Toaster and pals never really find this out.

They look up his name in the phone book and find his apartment shortly after he leaves it. (His girlfriend addresses him as "Rob," so I'm calling him that from here on.) There, Toaster and the gang are reunited with their old friend, Rabbit Ears. Rob still watches a black-and-white TV in 1987?

The number of the room is A-113, as in the number Lasseter likes to sneak into his films.

They haven't exactly made it from this point. They suffer feelings of rejection when they meet the newer appliances in Rob's apartment--newfangled, cutting-edge devices like the anthropomorphic Apple II shown to the left. The scene (and musical number) with these guys is easily the most dated part of the film. The giant dog-bone-handle phone sings about her "fiber-optics," big whoop.

Even worse, the new appliances know Rob was planning to use the old ones in his dorm and are steaming jealous over it. They kick Toaster and company out the window into the back-alley dumpster, where they'll be doomed in a junkyard unless Rabbit Ears can get Rob's attention.

While Rob and his girl are pondering where to pick up some cheap things (due to the old cabin being apparently robbed), Rabbit Ears frantically unleashes a series of increasingly loud commercial gimmicks advertising "Ernie's Disposal," which becomes "Crazy Ernie's Amazing Emporium of Total Bargain Madness!" Rob eventually takes the bait; meanwhile the old appliances are back at the junkyard, feeling worthless. Luckily, that's the title of the next and final song.

It's sung by the old junkyard cars as they expel their last exhaust before being smashed into scrap; they tell their life stories and their ultimate failures in what comes to be a pretty catchy blues tune. This one is usually mentioned as the favorite song of those that have seen the film.

After a string of teases against the audience, Rob finally finds his old appliances and prepares to leave with them. But just as he's picking them up, they're taken away by the giant magnet and deposited on a conveyor belt leading to a giant compactor--with Rob pinned down and headed for the same fate!

The ultimate climax of the film is the toaster saving its master's life by sacrificing itself in the gears of the compactor, shutting it down. This chews the toaster up pretty badly, ruining its chances of having any more appeal in its Master's eyes.

Or maybe it doesn't. It turns out the real reason Rob wanted the toaster was because it made good toast, the kind he couldn't get anymore from the newfangled cheap plastic models. He takes the time to repair the toaster and gets it working again, leading to a total happy ending.

In theory, at least. The only reason Rob wanted the other appliances was because he needed to stock his dorm; they're headed for inevitable heartbreak, and unlike Woody, they don't get a proper sequel in which they figure that out. (Note: this movie does have two sequels, but like every other animated film that existed already by the late 90's, its sequels were quick-and-cheap jobs taking advantage of the booming animated video market and contain no material worth your time whatsoever.)

The Brave Little Toaster isn't perfect. The story has one large inconsistency that doesn't make much sense if you watch the film looking for it. It's established early in the movie that the characters must carry a car battery around with them at all times, because Kirby needs to be plugged into a power source to move. Yet in the scenes before the battery is shown and in the scenes after they lose it, Kirby has no problem moving around.

There's also the fact that the jealous appliances in Rob's apartment automatically recognize Toaster and company as Rob's old things once they see them. Seriously, how could they know?

The Brave Little Toaster was Hyperion Pictures' first animated film, and would remain their best.

Their second movie was Rover Dangerfield. Toaster's the one that needs more respect.