1973 produced two significant things of note: The Exorcist, and the first issue of Cricket Magazine. Both made an impact on American society that can be felt to this day, but I only feel like writing about one of them.

As I've hammered into the ground by now (but I haven't written as many of these articles as it seems), Cricket was my favorite magazine as a kid and a huge influence in my own career. I appreciated that it didn't talk down to me the way other magazines aimed at kids did, and that its reason for being was to be as entertaining as possible, not force a lesson. After a rough day, getting a Cricket in the mailbox made you once again feel grateful you were born into this world.

Most of the information in this atticle comes from Celebrate Cricket: 30 Years Of Stories And Art, a hardcover treasury released in 2003 that we are very lucky to have, as it contains first-hand eyewitness accounts of Cricket's history from most of the founding members of this magazine, many of whom are now dead.

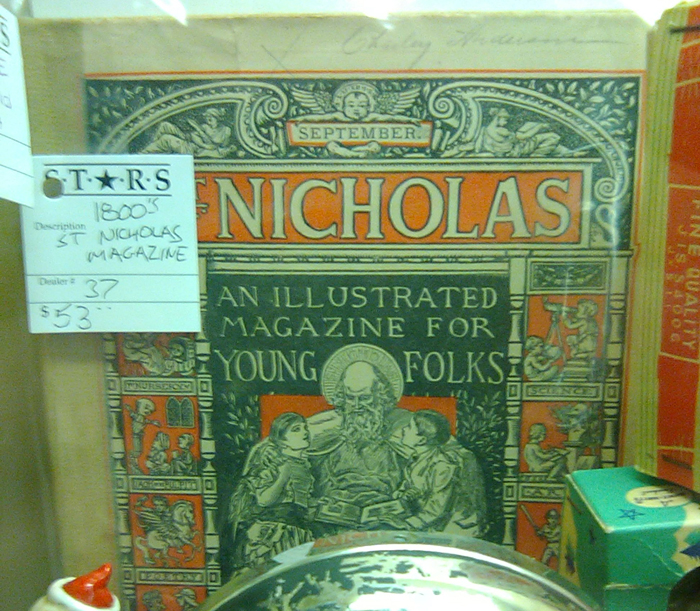

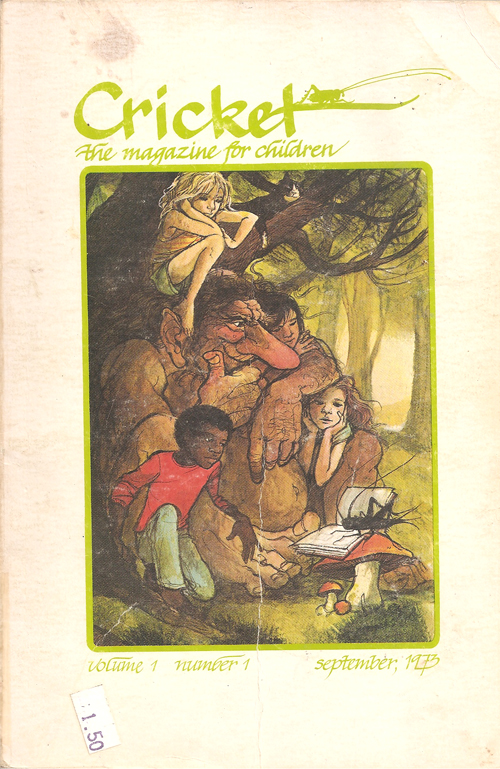

The germ of the idea was formed in the late sixties from Blouke and Marianne Carus, owners of the Open Court Publishing Company. Open Court produced textbooks for schools that contained short stories from children's authors. The Caruses noticed they received a common comment from the teachers they sold books to: there were no magazines for children that were actually ABOUT reading, or had the kind of stories that their books printed. Doing research, the closest thing Marianne Carus could find to such a magazine, IN ALL OF MAGAZINE HISTORY, was something called "St. Nicholas" that ceased publication in the 1930s.

Marianne tracked down back issues of St. Nicholas and felt deeply inspired by it, and decided she had to bring it back. All the stories were by professional authors of the day, illustrated by real big-shot artists, and not only that, the kids were allowed to send in stories of their own, as contest entries in a department called the "St. Nicholas League." Marianne told Blouke she knew what she had to do: create a modern St. Nicholas for the poor literature-deprived 1970s children.

They were in the perfect position to try this. The founding of Cricket is not an American Dream story where two people run a small business out of their garage. Cricket was born on third base by people that were already deep in the industry, who owned their own successful publishing house, and who already had established ties to EVERY major children's book author, as well as the mailing addresses of every public school in the United States. Cricket could have still failed by simply not catching on, but let's be real, this magazine happened because someone was powerful enough to make it happen.

As for where the title came from and what it means, the team considered names like Troubador or something describing a traveling storyteller, but they all sounded too cumbersome. They actually missed their deadline to provide a final name because they couldn't think of one, but one week later, Marianne was leafing through the childhood memoir of author Isaac Bashevis Singer and read this passage: "There was a little stove in Shosha's apartment behind which there lived a cricket. It chirped the nights through all winter long. I imagined that the cricket was telling a story that would never end." Story that would never end! Just like the magazine! It was a sign! That had to be the name!

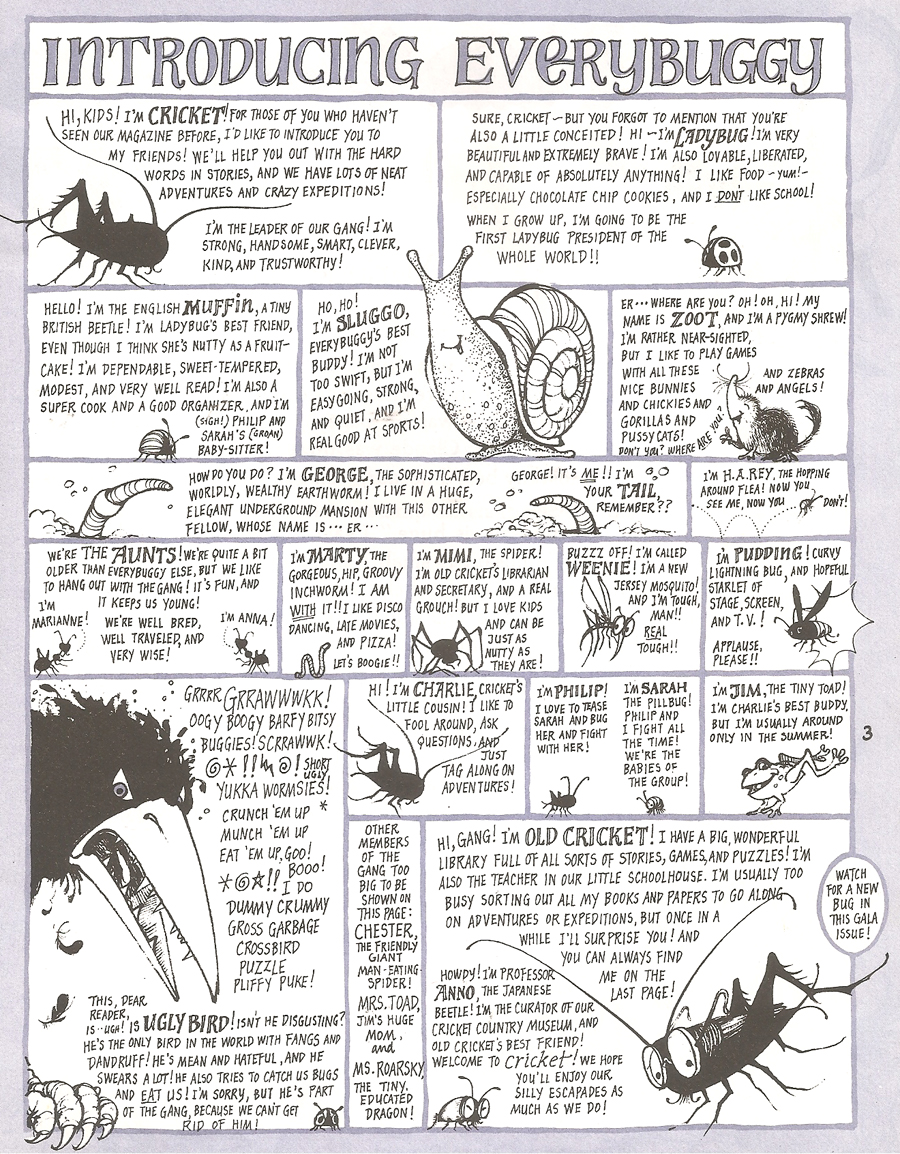

Of course, was naming the magazine after a noisy bug going to make sense to anyone unfamiliar with the works of Singer? Probably not, even though Singer himself was on the board of directors and would be contributing to the magazine many times over the years. Fortunately, the woman they had just brought on as art director had an idea about that...

Trina Schart Hyman had partial employment as illustrator of the Caruses' textbooks when she got the offer to work full time as the main art gal for their new magazine. At the first meeting with the head honchos and important people, Trina reached in her bag and slammed a jar full of live crickets onto the table, a "gift" she had hand-selected from the fields around her neighborhood. It was intended as a visual reminder to not take things too seriously. Up to that point Cricket was planned to just be an anthology of short stories with no real twist, but Trina insisted it had to be more than that. Also, the crickets got out. Because Trina opened the jar.

It's reading though Trina's account of Cricket's formative years that you realize just how indispensable she was to the success of this magazine and how it might not have felt half as special without her. Since color was expensive in those days, they had planned to print Cricket entirely in black and white, but Trina gave them the idea of overlaying one specific color per issue. And there were no initial plans to do a comic strip or add bugs all over the page. When Trina first put the idea forth, she was met with resistance from everyone in the room, with the exception of Lloyd Alexander (the Prydain guy, with the big nose).

Undaunted, Trina laid down a piece of paper and started her first drawings of what would become Cricket and Ladybug so everyone could see what was in her head. She then concocted samples of the strip and showed them to the board, and only then did they start warming to the idea. Blouke Carus wanted defintions of difficult words in the stories to be printed in the margins. Trina thought the base idea was too "dry" and livened it up with the suggestion that the bugs could appear on the pages and define the words themselves. Cricket was starting to develop something key to its success, that no other children's magazine had to date: a personality.

And I mentioned last time I talked about Cricket how much of the first issue's content came solely from Trina herself. Cricket didn't pay very well, and Trina was already an established illustrator and didn't NEED the gig. But she put 175% of herself into this magazine to make it as entertaining as it could be. Trina busted her ass to make Cricket what it became, and it's too bad I can't thank her for it, because she has been dead for quite a while!

A "pilot" issue of Cricket was shipped out to schools across the country in January of 1973 with a plea for support. The pilot was largely the same content as the first issue that would be shipped that September, albeit a lot more hand-drawn. Artist Jan Adkins was most known for his calligraphy skills, and not only created the Cricket logo and the logo of every department, but the entire table of contents was also hand-calligraphied. This was something kids found hard to read and teachers suggested be changed. Trina admitted the pilot issue's layout was too "hippie" and came up with some traditional layouts for the actual first issue.

During the month of Cricket's debut, the Caruses hosted a launch party in New York City at the St. Moritz Hotel and invited every single person they knew in the industry -- artists, writers, publishers, agents and anyone remotely connected. Later on, Marianne received this comment from one of the attendees: "if a bomb had gone off during your party, the entire children's book world would have been wiped out."

Since the target market at first was schools, the magazine started on a nine-month-a-year schedule, with no issues being published in June, July or August. To the editors' surprise there was backlash against this -- the magazine had gained steam in US homes quickler than they figured, and many parents wrote to them wondering why Cricket didn't publish in the summer. Cricket only stuck to the "hiatus" for two years, moving to 12 issues a month in September of 1975.

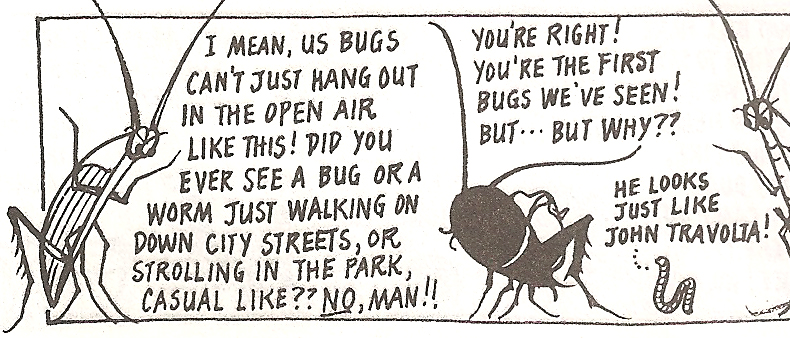

Marty the inchworm makes a current pop culture reference, July

1979

Trina was only Art Director until 1979, but kept doing the bug strip she had created until 1987, at which point she started feeling fatigue. "The cartoon was a lot of fun up to a point," she remembered, "and then it got to be work." She said by the end she was having fantasies about a giant foot coming down and smashing the entire cast so she didn't have to write anymore. That was, uh, when she knew she had to quit. But who could take her place?

Trina's final bug strip, December 1987

Jean Gralley's art is so similar-looking to Trina's I had always assumed they grew up together as children or something, but the actual story of their meeting is a bit...harsher than that. Jean's initial contact with Trina was when she was fresh out of art school and looking for employment. She sent Trina a folder full of drawings approved by her art teacher: shaded spheres, crosshatched cones, intimate studies of three-dimensional shapes and the shading thereof. Weeks later, a personal letter from Ms. Hyman was mailed back to Jean -- an angry one full of expletives, declaring this to be one of the most worthless portfolios for a children's art career she'd ever seen.

That really could have been the end of it right there, but Gralley decided to meet Trina's challenge for "real" art and sent another set of drawings, this time of actual people -- who were waiting eagerly by a mailbox for their reply from Trina Schart Hyman. A caricature of Gralley herself reads the reply letter verbatim and everyone's face falls. Characters weep buckets. A child wails, "What do we do now?" If Hyman was going to go for her throat, Gralley was going to lunge right back.

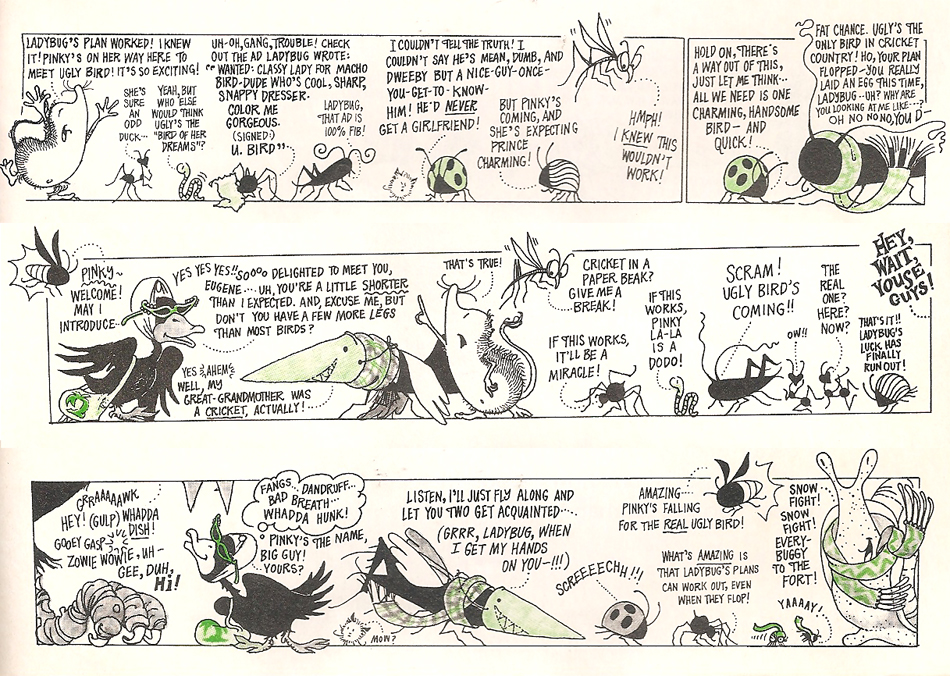

This ballsy kickback met Trina's demented approval ("That's the spirit!") and Gralley started receiving offerings for illustration work. And then, eventually, when Trina was in bug-squashing mode, Gralley was the one she invited to take her place to save their little lives. Trina ended up doing the strip for fifteen years; Gralley would take it further for another fifteen. My time with Cricket encompasses the majority of Gralley's run, having picked the mag up in 1990 (she started in 1988) and having cancelled it in 2003 (the same year she quit).

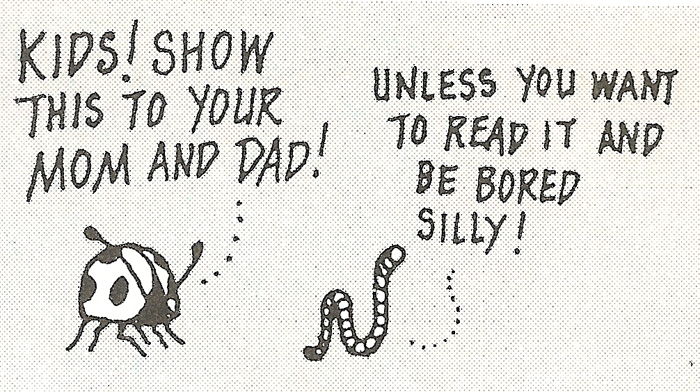

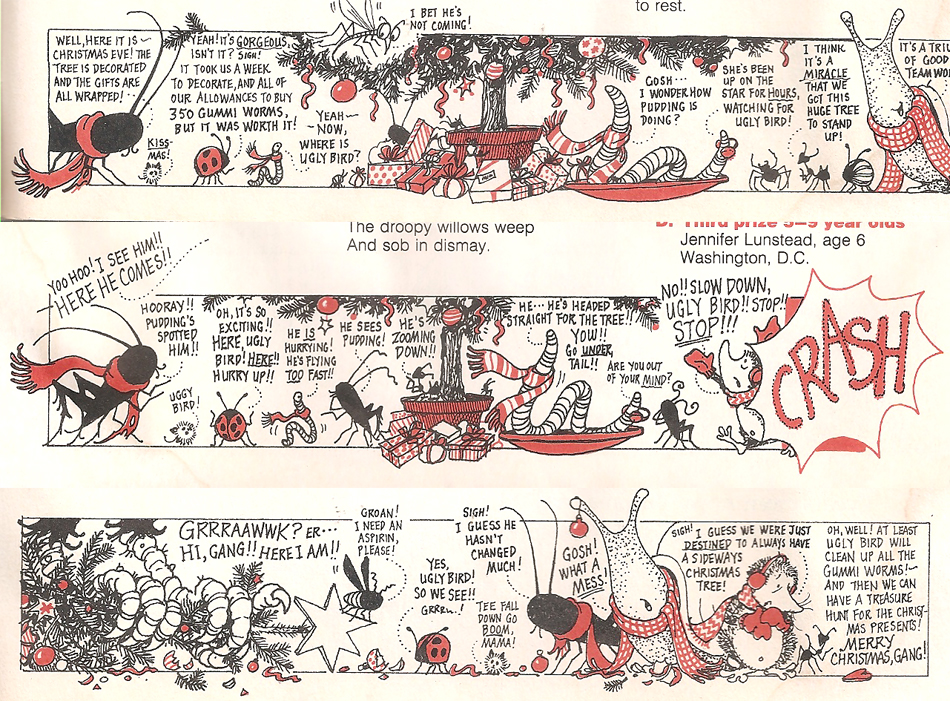

A memorable sequence of Gralley's from March 1990, the first

issue I received in the mail

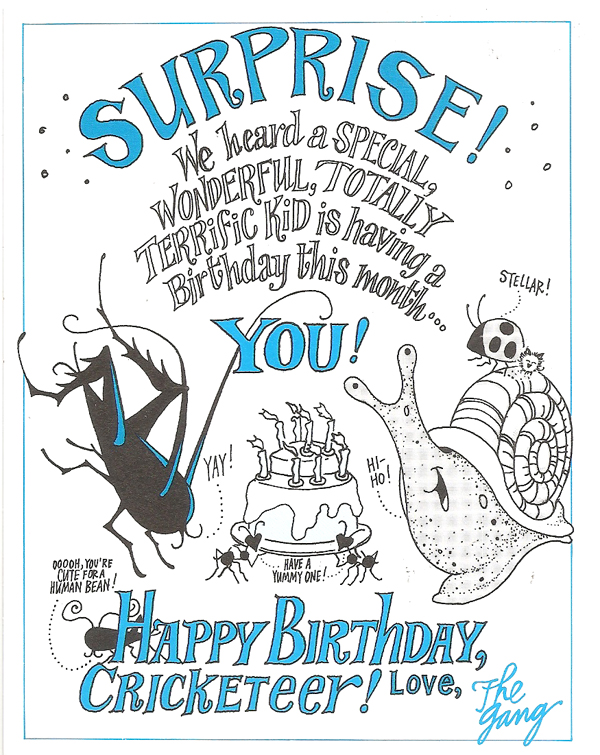

Nothing demonstrates how eager Cricket was to build a relationship with their audience than this: in 1992, the magazine tucked thousands of these cards into readers' issues on the month of their birthdays. Not an advertised feature, done with no prior warning, and they only did this ONCE. They guessed my birth month correctly, and I have no idea how they did it.

I've checked back in on Cricket every now and then, and if the darn thing is now 50, it would seem it's once again time. While some things in the latest issues are different, others remain the same. For one thing, despite the contraction the print industry has gone through in recent years, ALL the additional spinoff magazines Cricket put out in the 1990s are still alive and running today, even Babybug, the magazine for babies. I never expected Babybug to survive because the concept is so loony ("Give your children the gift they'll never remember!") but here it still is, nearly thirty and flirty and thriving.

However, that contraction did hit all those magazines in one way: they all have less pages. Cricket used to be 64 pages; it's now 48 pages. Spider was once 48 pages but it has shrunk to 32, while Ladybug was reduced to 24. In my opinion, Cricket needs to be AT LEAST 64 pages if they expect kids to get fully absorbed in it, no matter how much that would cost in 2023 money.

And that's just one of several opinions I have. Here is a fairly recent issue I found stuffed into a Little Free Library, from a child who evidently wasn't as enamored with it as I was at that age.

Those maniacs. They really did it.

The publishing company has been using this "new" Cricket logo for a while now on promotional materials and ads, to signify the operation as a whole (it's now called the "Cricket Magazine Group"). But until now, they've never dared to break tradition, whiz on Jan Adkins' burial site and slap that logo on the magazine itself because...I mean, look at it. Look at how much of the cover art that honker is blocking. Highlights would do this; you guys are supposed to be smarter than Highlights.

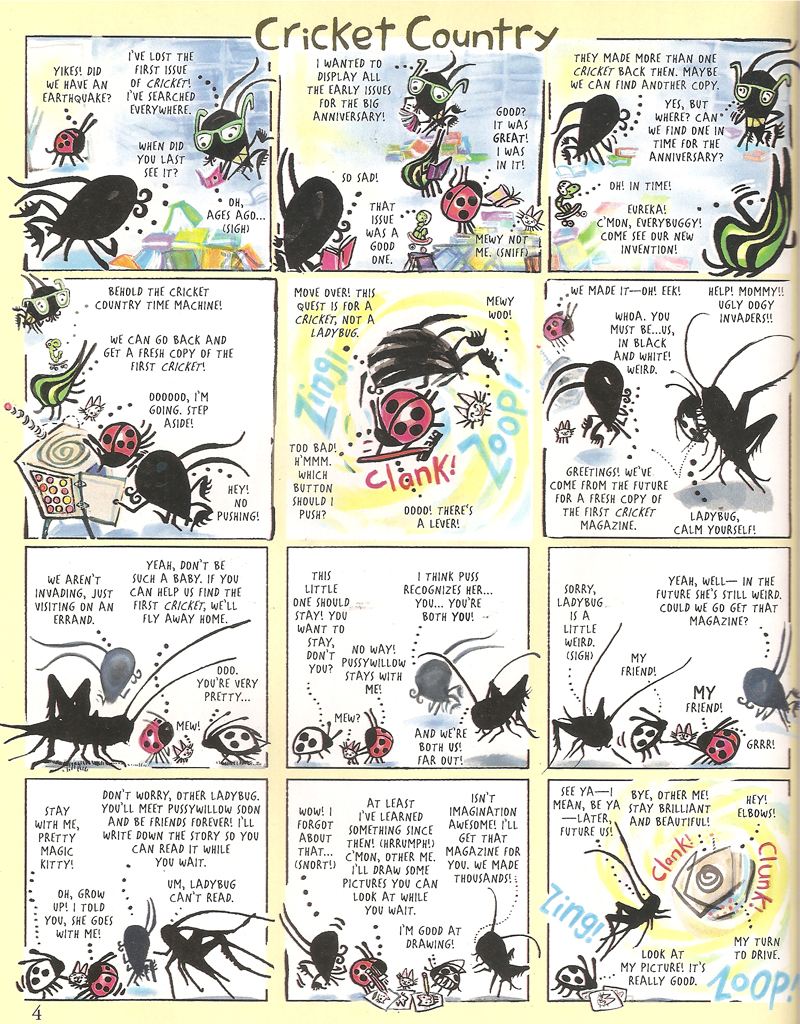

I've said in the past that I don't care for the version of the bug strip done by Caroline Digby Conahan. She's still there, and...I still don't. I guess it doesn't matter what I think because Caroline has now been there longer than any previous bug strip artist, and there are now full-grown adults who are only familiar with this version of it, and so it'd be a matter of my nostalgia against theirs. But I feel the evidence is on my side. Gralley's bug strip was both heartfelt and hilarious, with wit for days, while Caroline's art is a complete whirlwind of a mess and her dialogue is flatter than most pancakes. Let's remember I got this issue because a kid threw it out. They'd never have thrown out a Gralley-era Cricket.

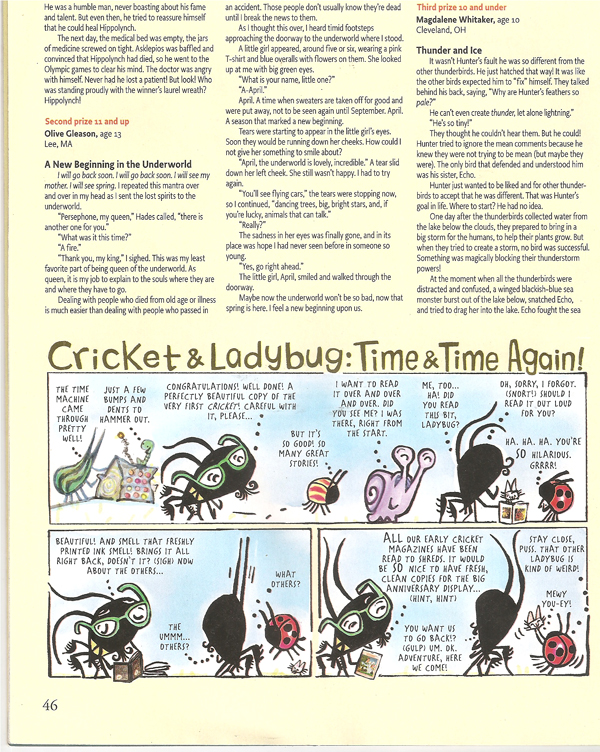

To make matters worse, the strip isn't even a strip anymore! 90% of the story in each issue has been shoved to one page. "Cricket and Ladybug" is still there, but it's almost redundant now, only serving to resolve loose ends from the one-page story at the beginning of the book. The bug strip is supposed to be a FRAMING DEVICE. The story is supposed to start in Letterbox, continue in "Cricket and Ladybug" and conclude in Cricket League. Each issue has its own story that wraps around the book! That's how it's supposed to be! You don't read the story and THEN the issue! Trina's intended format is broken if you do it this way!

This seems to be Part 1 of an anniversary story where Cricket and Ladybug travel into the past to meet the original versions of themselves. But since Conahan can't draw the original Cricket and Ladybug very accurately, it's difficult to tell who is who (aside from coloring). Maybe she should've just pasted Trina's old art into the panels. Or was that allowed?

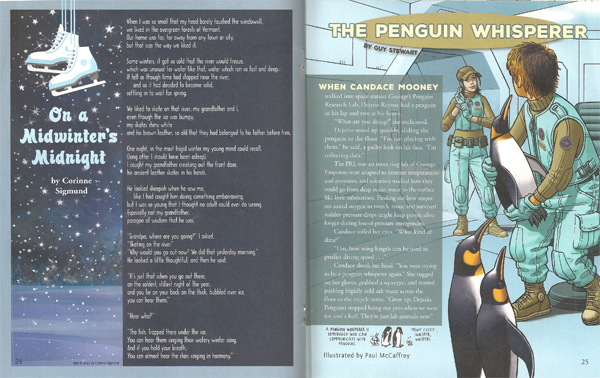

The stories in the book are still good. It's pretty hard to mess THAT part up. There's just, unfortunately, less of it due to the smaller page count.

I guess I just have to accept that if you do something for fifty years, it's very unlikely to stay the same. Sesame Street, for example, has lost a lot of the wry Henson spark that was originally in it. It's been the Elmo Show since 1997 and is more obsessed with being cute than funny. Founders die, and the new class has different ideas, and they're not always as inspired.

But I still have all my old Crickets and in terms of content and quality of the stories therein, they haven't aged a day. I can see a kid today getting just as much a kick out of them as I did, and still do. But if their only impression is the watered-down thing produced these days, I fear they won't get it. I still love Cricket, or the basic idea of it, but not everybuggy might understand that love. And that's a purry shame.